CDF (Caroline De Frias)

“Caroline DeFrias (CDF) is an artist-academic-curator currently based in Tiohtià:ke (Montréal). Their work is interested in notions of inheritance and identity in relation to immigration and (re)settlement; queer identity and the process of aging and memory making; the construction of the gallery space, politics of display, and the encounter of the object; as well as the ethics and pathos of the archive. CDF’s current practice operates through a hybrid of mixed-media/film photography, operating somewhere between distance and intimacy as they (re)present their subjects, creating images of twofold representation.

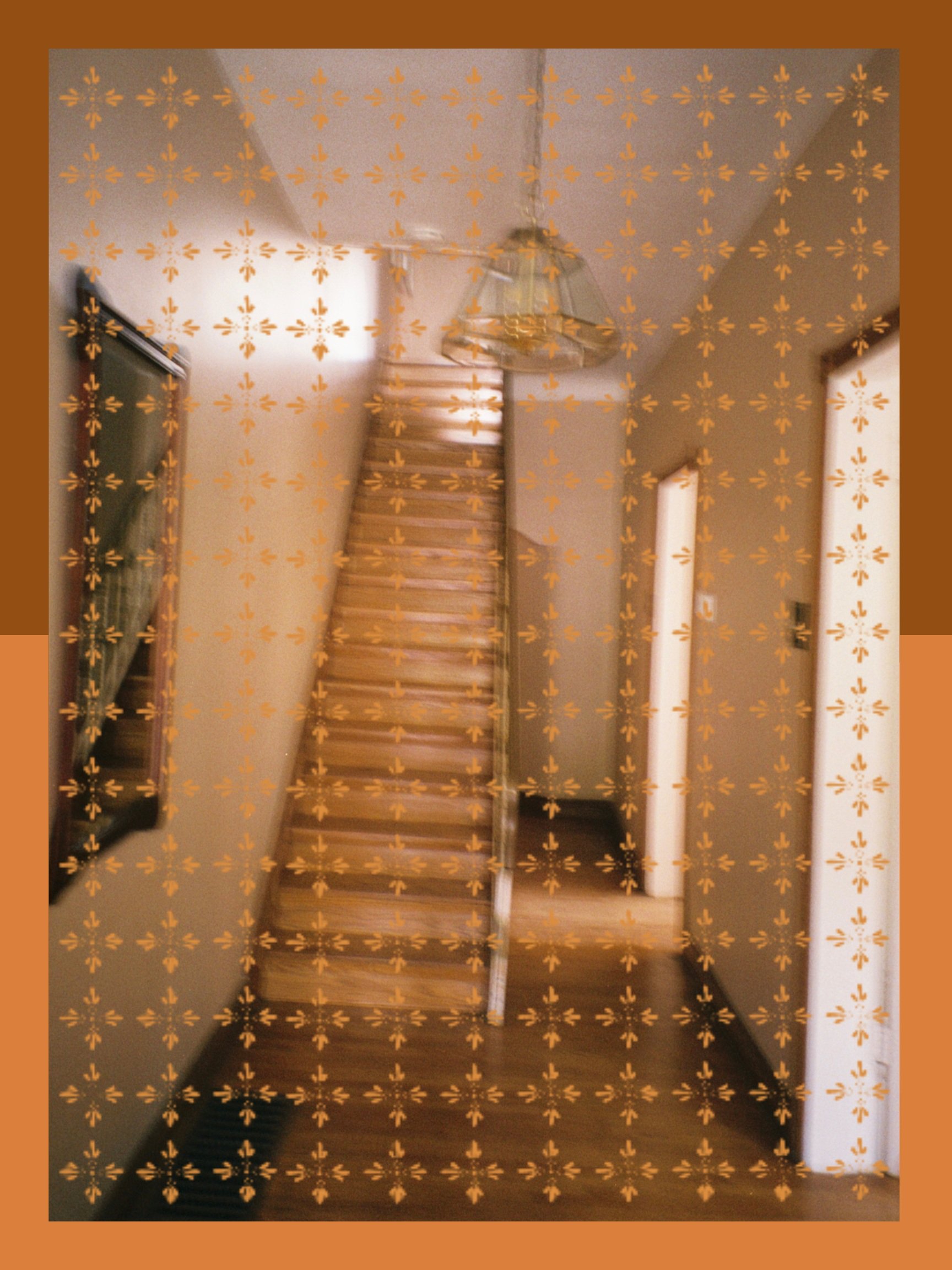

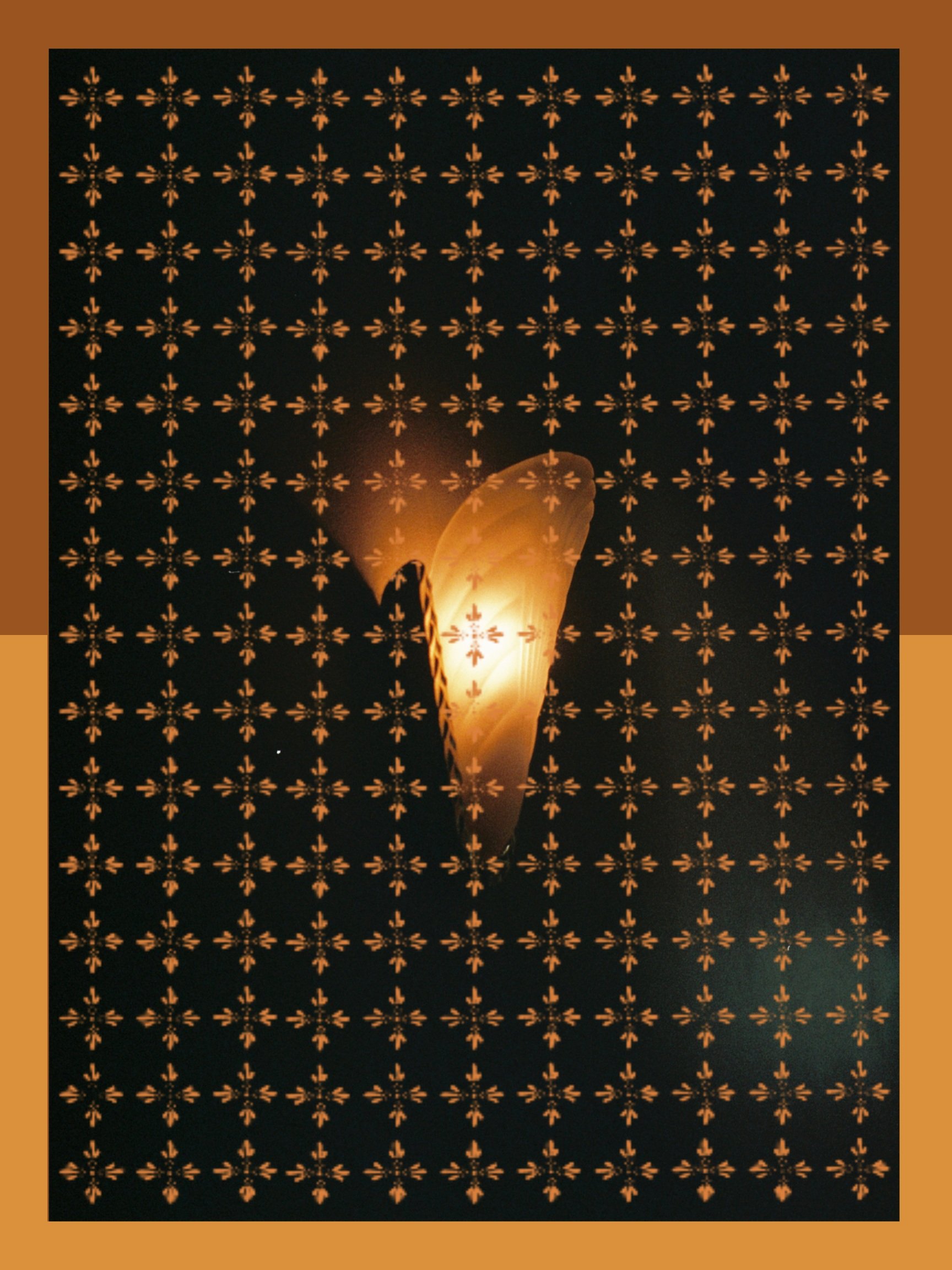

In their featured series, “Os Mitos da Casa da Vovó” (The Myths of Grandma’s House), CDF seeks to locate childhood somewhere between memory and daydream. A traditional azulejos pattern lays like lace overtop 35mm photographs taken of their grandmother’s house, the first and only house their paternal grandparents inhabited in Canada and the site of many of their own childhood memories. The sketches seem to guard these images like a fence, separating the viewer from an easy reading of this precious space and encouraging a recognition of the otherwise hidden or forgotten stories and lives contained quite literally between the lines. The repetitious design intervenes on behalf of the sunday afternoons, the grapes that grew in the summer, the creaky eleventh step, the burning chocolate chip cookies in the oven, the monsters in the basement closet, and three generations of folklore.”

An Interview with CDF

“I think at this stage and time of my life where I’m busy with my MFA, my favourite type of piece to create is one I can laugh during the process.”

Ciara: You have worked in design, film, curation, among other disciplines. What title would you give yourself for what you do and what is your main focus?

CDF: I find the order changes constantly, but currently I think of myself as an academic/curator/artist, kind of floating in and out of whatever discipline and medium best facilitates the ideas I’m working through. Currently, I’m interested in notions of inheritance and identity in relation to immigration and (re)settlement; queer identity and the process of aging and memory making; the construction of the gallery space, politics of display, and the encounter of the object; as well as the ethics and pathos of the archive. It might sound like a lot, but to me these feel interconnected and converge on critical sentimentality.

Ciara: I love your themes of memory, (re)settlement, inheritance, and the archive in your work. What inspires you to focus on the themes you portray?

CDF: I come from an immigrant family—my parents are both the first, and for my mother, the only members of their family units to be born in Canada. In my extended family, virtually everyone above my generation immigrated from the Azores—the Portuguese islands in the middle of the Atlantic—and so I was raised nostalgically on stories and (re)constructions of home while simultaneously witnessing the bleaching of this cultural identity as my family assimilated into settler Canadian culture. I think it’s very second-generation-born-in-Canada for me to be preoccupied with questions of (re)settlement, inheritance, memory and identity. I wouldn’t say that I’m interested in restoring, returning, or replicating the visual or aesthetic languages and history of my cultural heritage, but learning to stay and live with the trouble of inhabiting many evolving identities.

Ciara: Biggest Inspiration?

CDF: I am constantly thinking about and in awe of artists Agnes Martin and Marlow Moss. Agnes Martin was a minimalist best known for her grids: a set of horizontal and vertical lines drawn meticulously with a string to guide her pencil on canvases six feet high and six feet wide. Marlow Moss was a constructivist artist concerned with ideas of perpetual becoming; they are best remembered for their contribution of the double line to constructivist aesthetics whereby they placed parallel lines in close proximity to one another in their geometric compositions, a queering of constructivist aesthetic which they believed gave energy to otherwise static single grid neoplasticism works like those of Modrian. Both are queer artists who utilized a more abstract visual language: line, geometry, colour, as opposed to figures and forms. As a queer person, I often find this a more accessible way of encountering the world and my self: that composition principles and gestural vocabulary are more reliable categories of understanding than binary language of gender and subject.

Ciara: Favourite type of piece to create?

CDF: Currently, I’m primarily working with film photography and development. I’m having a lot of fun experimenting with exposure, expiration, and organic chemical baths for my film to see what sort of results I can produce. I’ve also gotten back into sketching and am working on a few stop-motion animations for fun. I think at this stage and time of my life where I’m busy with my MFA, my favourite type of piece to create is one I can laugh during the process.

Ciara: How did you get into the arts?

CDF: I have been really fortunate to grow up in galleries. Since I was a young child, for as long as I can remember, my parents took me to every gallery or museum that they could. It was really important to my family that I understand the value of history and community and so I was exposed to art at a young age which fostered my passion. I have the privilege of encouragement and support from my family. I have this fond memory of being in my mom’s office as a young kid, and on her breaks we would google artists and learn together. I don’t come from an artistic family with anyone really interested or working in the industry, but for my birthday everyone would get me pencils, crayons and sketchbooks because they knew that I was, and it took off from there.

Ciara: How did you get into curating and graphic design?

CDF: The gallery has and continues to inspire a profound sense of wonder and curiosity in me, since I was kid. But as I grew older and became a political person, I began to contend with a growing awareness, which became my area of study, into the harm gallery spaces have historically and continue in the present to perpetuate against racialized, colonialized, and minoritized communities. I recognized the role of the curator, as the collector and organizer of these spaces, as vital within the continued transmission of colonial and capitalistic violence in the gallery. I fell into curating as a means of challenging my nostalgia and reverence for the gallery; it was a way for me to use and channel the passion and knowledge I gained in this space to make it more accessible and dismantle it when needed. How and what we display in institutions of knowledge/power is critical, and I find that I am very passionate about examining and participating in decolonial efforts within this field.

Ciara: What is your dream job?

CDF: I am very passionate about decolonial efforts in general, but I have a specific motivation for this work in gallery spaces. My dream job is to work collaboratively to create novel and changing visual display practices based in justice and the ongoing processes of reconciliation and decolonization. I’m not sure precisely where I will find myself or what position(s) I will share, but if it was my job to support individuals doing this work, even if I was the one making dinners or grabbing coffee, I think I would be tremendously happy to do whatever I could to help and support this work.

Ciara: What era/movement do you find the most intriguing/inspirational in art?

CDF: Currently, I’m fascinated with the beginnings of film—I’ve been watching a lot of Eadweard Muybridge and Alice Guy-Blanché. Watching the first moving images and seeing what we thought to capture, what stories were told, is very fascinating. And with Muybridge it’s also a very participatory practice if you decide to look into his work because he made a great deal of photograph plates to capture movement frame by frame and not all of them are publicly accessible as animations so I’ve spent a few nights on photoshop and with a printer making flip books to bring his works to life which almost overwhelms you with gratitude for the gift that is the moving image—that is film. And Alice Guy-Blanché was a pioneer of early cinema and the first woman director, and she is acknowledged as the first director to film a narrative story. I think art is remarkable for its ability to communicate and document complex ideas, histories, identities, and values. And looking at early cinema I think it’s really wonderful to reflect on all the work and innovative ways of communicating that we have made since.

Ciara: Do you have any advice for people starting out?

CDF: Make as much as you can, even if you’re worried your ideas stink or your technical skills aren’t where you want them to be, and learn as much as you can, even about artists and works you don’t like. I often struggle with the former. I overthink and critique my ideas as if there are objects standing in front of me and this often stops me from producing as much work and gaining as much technical skill as I could if I trusted the process and myself more. There is something wonderful about what you learn about yourself and your practice when you make terrible art, and I’m trying to take myself less seriously and build my practice on joy. For the latter, there is nothing more inspiring than other artists and art works and no better way to leave a slump than by introducing yourself to new ideas.